The Marmara region of Türkiye, situated at the meeting point of Europe and Asia, harbors a silent yet growing threat deep beneath the waters of the Marmara Sea. Though the region appears calm on the surface, it sits atop one of the most active seismic zones in the world – the western end of the North Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ), a massive tectonic boundary responsible for some of the most destructive earthquakes in the country’s history.

At the heart of this fault system lies the Main Marmara Fault (MMF), an underwater fault located just a few kilometers south of Istanbul, one of the world’s most populous and economically vital cities. We, seismologists, have long warned that this fault, locked and accumulating stress for centuries, could be the source of Türkiye’s next catastrophic earthquake. And recent events have once again brought that danger to the forefront of public attention.

The NAFZ is the physical boundary between the Anatolian Plate, which covers most of Türkiye, and the Eurasian Plate to the north. Driven by the ongoing collision of the Arabian Plate from the southeast, the Anatolian Plate is squeezed westward, scraping past the Eurasian Plate at a speed of about 20-25 millimeters per year. This motion creates intense friction and stress along the fault, particularly in its westernmost sections, including the Marmara region.

The right-lateral behavior of the MMF, and more broadly the North Anatolian Fault (NAF), is similar to that of the San Andreas Fault. However, unlike the relatively straightforward faults commonly found in places like California, the MMF is anything but simple. It features complex geometry, varying depths, multiple fault branches and an irregular stress distribution – all of which make predicting its behavior especially challenging. Adding to the complexity, the MMF lies beneath the Marmara, which significantly limits scientists’ ability to study it through direct, land-based observation.

History of earthquakes along MMF

The 20th century witnessed a remarkable sequence of large earthquakes propagating westward along the North Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ), beginning with the devastating 1939 7.9 magnitude Erzincan earthquake, which claimed over 30,000 lives. One by one, fault segments snapped – Tokat (1942), Bolu (1944), and continuing west until the 1999 Izmit (M7.4) and Düzce (M7.2) earthquakes, which together caused more than 18,000 deaths.

However, one major segment was left untouched: a 120-kilometer stretch beneath the Marmara, known today as the Marmara Seismic Gap. It lies between the rupture zones of the 1912 Ganos earthquake in the west and the 1999 Izmit earthquake in the east. This segment has not experienced a major rupture since at least the 18th century, and its proximity to Istanbul – only about 8 kilometers from the densely populated southern coastline – makes it an ever-present risk.

Significance of April 23

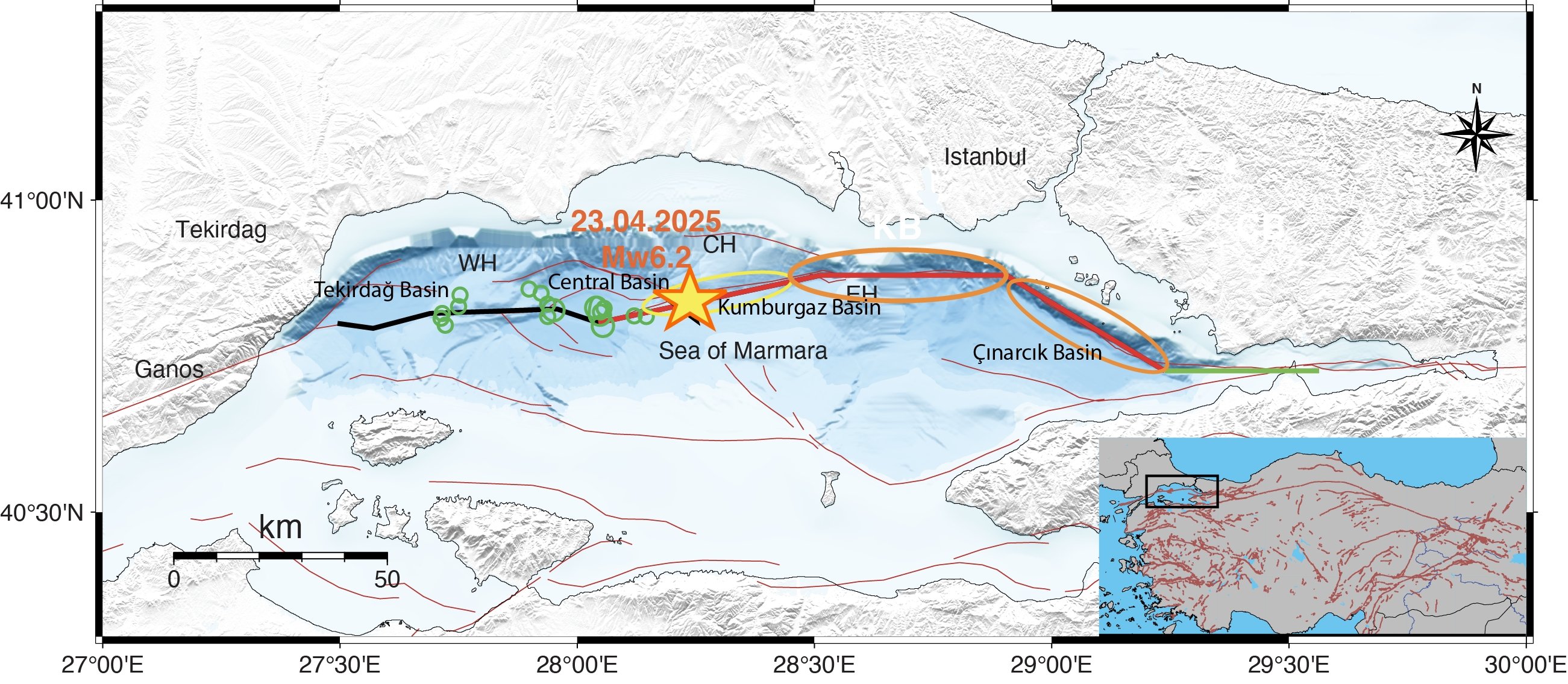

On April 23, 2025, the region was shaken by a magnitude 6.2 earthquake, centered on the Central Marmara Fault, a branch of the Marmara Mega Fault (MMF). While this event did not cause major devastation, it served as a stark reminder that the MMF is not dormant – it is active and dangerous.

According to seismologists, the quake ruptured a fully locked segment of the MMF between the Central Marmara and Kumburgaz Basins, releasing part of the accumulated stress. However, two adjacent fault segments – the Kumburgaz (Avcılar) and Princes’ Islands faults – remain unbroken to the east, raising concerns that they could be the sites of future large earthquakes. Additionally, some areas of the Central Marmara Basin to the west are also at risk, as they have not experienced a rupture since 1766.

Together, these segments are believed to be capable of generating a magnitude 7.0 to 7.4 earthquake, similar in strength to the 1999 Izmit disaster. The key question now facing scientists, city planners and the public is: When will they break?

Potential scenarios

Earthquake recurrence intervals – the frequency at which a fault segment typically ruptures – are crucial for estimating future risk. Historical records and sediment layers from the seafloor suggest that the MMF experiences major earthquakes roughly every 250 years. The most notable sequence occurred in 1766, when two massive earthquakes just months apart are thought to have ruptured much of the MMF.

However, pinpointing the exact locations and timings of past ruptures remains a challenge. For example, the 1894 earthquake is believed to have occurred near the Çınarcık Basin, which is bounded by the Princes’ Islands Fault to the north and another fault to the south. However, the exact rupture area (fault) is still debated among scientists. These uncertainties make it more difficult to accurately model the fault’s behavior and forecast its future activity.”

To tackle this problem, we have conducted 90 advanced 3D dynamic rupture simulations, each exploring different scenarios of how stress might be released along the Main Marmara Fault (MMF). These physics-based models take into account fault geometry, historical data and real-geodetic observations.

Our simulations suggest two main scenarios for the next major earthquake:

If the Prince’s Islands Fault last ruptured in 1766, it has now exceeded its expected recurrence interval. In this scenario, the Prince’s Islands and Kumburgaz Basin faults (also referred to as the Avcılar Fault) could rupture either independently in two quakes around 7.0 in magnitude or jointly as a result of stress transfer from a rupture on the neighboring Kumburgaz segment, producing a 7.2 earthquake or larger.

If the last rupture occurred in 1894, the Prince’s Islands Fault may not yet be ready to fail again. In this case, a rupture on the Kumburgaz segment could terminate before propagating eastward, allowing stress to continue, accumulating on the Princes’ Islands Fault for several more decades.

In the most extreme scenario – where all remaining segments rupture simultaneously, including the portion that broke on April 23, 2025 – the resulting quake could reach magnitude of 7.4, a level of energy capable of causing widespread destruction across the Marmara region.

Adding another layer of concern, the Prince’s Islands Fault dips at an angle of approximately 70 degrees – unlike most vertical strike-slip faults. This geometry results in a vertical displacement of several dozens of centimeters during an earthquake. When combined with the potential for underwater landslides, it significantly increases the risk of tsunami generation. A major rupture along this fault could produce waves several meters high, threatening Istanbul’s southern coastline, including densely populated neighborhoods near the Bosporus Strait. Such an event could disrupt maritime traffic and have serious consequences for coastal communities.

Our dynamic earthquake rupture simulations indicate that ground shaking during a large MMF earthquake would be most intense in the Marmara Ereğlisi district on the Marmara coast and along the southern coast of Istanbul’s European side, mirroring the patterns observed in the 2025 6.2 magnitude event. This reinforces the idea that high-resolution modeling is not just academic – it provides critical guidance for emergency planners and architects designing earthquake-resistant infrastructure.

Urgency to prepare

With nearly 25 million people living in and around the Marmara region – including Istanbul, Tekirdağ, Yalova and Bursa – the stakes could not be higher. A major earthquake would not only cause immense human loss but also disrupt Türkiye’s economic engine, paralyze transportation and logistics and potentially damage historic landmarks and critical infrastructure.

The MMF represents one of the most thoroughly studied, yet most unpredictable, earthquake sources in the world. While we cannot say exactly when the next major quake will strike, all evidence suggests that the risk is high and growing.

The good news is that science is evolving. With improved data from satellite GPS, seafloor sensors and more sophisticated computer models, our understanding of the MMF is clearer than ever before. But knowledge alone is not enough.

The people of the Marmara region – and the policymakers who serve them – must act decisively. Earthquake preparedness, tsunami planning, public education and rigorous enforcement of building codes are no longer optional. They are essential.

Only through a combination of scientific insight and societal action can Türkiye reduce the damage from what may be the most inevitable natural disaster in its modern history.