Iraq occupies a strategic position in Middle Eastern politics, making it a pivotal axis for regional and global powers. There are at least three key factors that underline its relevance: its unique geopolitical and historical profile, its disproportionate influence on Arab politics, and its cosmopolitan demography and vast hydrocarbon reserves. Iraq’s civilizational strength is evident in the ruins of ancient Mesopotamian civilizations, including Babylon.

Historically, Iraq has symbolized Arab resistance, exemplified by Saddam Hussein’s assertive foreign policies and the country’s protracted war against Iran (1980-1988) and confrontation with Israel and the United States. The country’s diverse sectarian and ethnic identities – Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Sunnis, Shiites, Christians and others – have made it a focal point for political, economic and military interventions.

My field research conducted in Baghdad, Fallujah and the Najaf-Karbala corridor included interviews with political actors, academics and local stakeholders that provided a firsthand perspective on Iraq’s internal dynamics and regional entanglements. These insights reveal how Iraq’s fractured governance and competing external influences continue to shape its post-2003 trajectory. The Development Road project is particularly interesting, a significant infrastructure initiative symbolizing Iraq’s search for regional agency and economic recovery. Framed within Iraq’s sectarian legacy and foreign interference, this analysis explores how domestic fragmentation, Iranian-Turkish competition, and regional rivalries intersect to shape the country’s future. The Development Road is not merely a logistical project but a barometer of Iraq’s capacity to move from conflict to cooperation.

The legacy of authoritarian governance, foreign interventions and ethno-sectarian engineering continues to shape Iraq’s fractured political landscape. Saddam Hussein’s regime marginalized the Shiite population, excluding them from critical roles in state institutions. The 2003 U.S. invasion triggered a dramatic shift, leading to the establishment of a Shiite-centric order under the 2005 Constitution. While framed as democratization, this American-led transformation reproduced the logic of exclusion in reverse, this time marginalizing Sunnis.

What emerged was not inclusive governance but a new form of sectarian authoritarianism. Many Sunnis became politically alienated, contributing to the radicalization that enabled the rise of extremist groups like Daesh. The U.S. occupation entrenched sectarian divisions and accelerated the collapse of state cohesion. This vacuum allowed external actors to exploit Iraq’s vulnerabilities for strategic gain.

Contested landscape

Among Iraq’s most influential external actors are Iran and Türkiye, two powers with distinct strategies. Iran’s influence, especially among Shiite groups, is deep-rooted and cultivated through religious, ideological and educational networks. In contrast, Türkiye’s approach emphasizes development, infrastructure, trade and education, illustrated by initiatives like the Maarif Foundation schools.

While Türkiye avoids framing Iraq as a zero-sum arena, Iran’s hardline factions pursue a more assertive posture to counter Turkish influence. Yet, field interviews indicate that anti-Turkish sentiment remains limited among Iraqi Shiites. Notably, forecasts suggest that Shiite political dominance may weaken in the 2025 elections. This is a shift that could redefine Iranian leverage in Iraq.

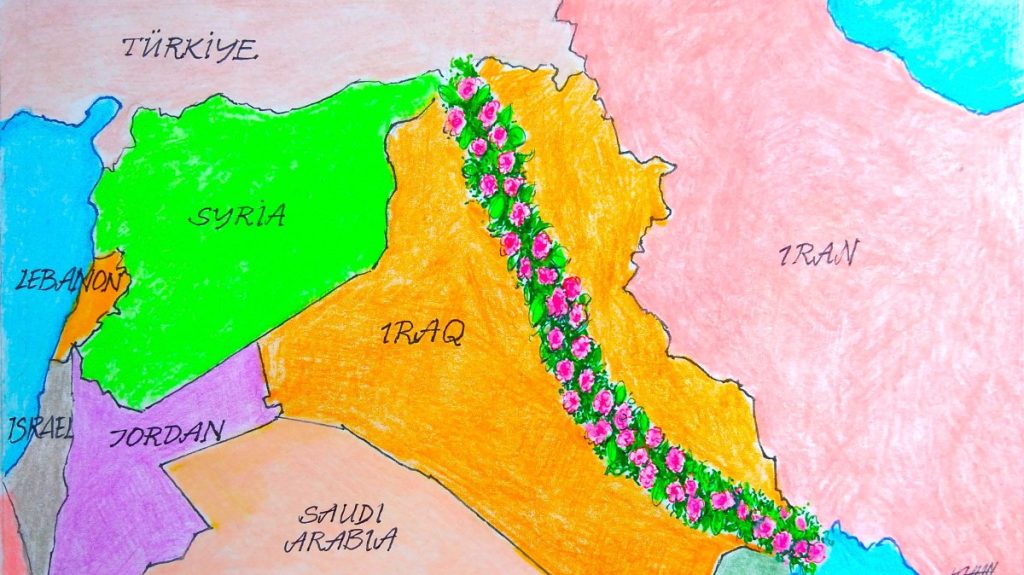

The Development Road initiative between Türkiye and Iraq aims to create a multi-modal corridor connecting Basra’s Grand Faw Port to the Turkish border and European markets. It presents Iraq with a historic opportunity to become a logistical hub linking Asia and Europe, offering an alternative to maritime routes like the Suez Canal and Haifa Port.

Yet, this promise is entangled in Iraq’s internal divisions. Disputes between the federal government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over the route and economic benefits have stalled progress. The KRG demands that the corridor pass through Kurdish-controlled areas to ensure equitable participation, while Baghdad remains noncommittal. These tensions mirror unresolved issues like oil revenue sharing and reflect deeper dysfunction within Iraq’s federal system.

Regionally, the project has triggered strategic concerns. Egypt fears competition with the Suez Canal. Israel, reliant on the Haifa Port, sees its regional relevance waning, especially after Oct. 7. Iran’s reaction has been more reserved; although the corridor bypasses its territory, Tehran may benefit indirectly.

Who offers what?

Iran’s silence on the Development Road should not be mistaken for disinterest. Tehran’s cautious stance reflects a strategic calculation. First, the project could stabilize Iraq by creating shared economic interests across sectarian lines, aligning with Iran’s desire for a secure western flank. Second, it may stimulate growth in Shiite-majority cities like Najaf and Karbala, which have strong religious and cultural ties to Iran. Third, Iran retains strategic leverage through its control of the Strait of Hormuz and regional trade routes. Tehran’s reaction contrasts with its vocal opposition to the Zangezur Corridor in the South Caucasus, suggesting that Iran views the Development Road as complementary rather than competitive, as long as it does not undermine Iranian economic interests.

Türkiye has emerged as the leading architect and guarantor of the Development Road. Its diplomatic strategy emphasizes multilateralism and avoids excluding key Iraqi stakeholders, including the KRG. Ankara frames the corridor as a win-win venture, consistent with its broader regional normalization strategy, as seen in its rapprochements with Gulf states and pragmatic relations with Iran. Türkiye’s counterterrorism operations in northern Iraq and Syria, alongside its domestic political recalibrations, also contribute to the corridor’s security framework. International actors, including former U.S. President Donald Trump, have voiced cautious optimism about Türkiye’s stabilizing role in the region.

Field research and regional analysis highlight that Iraq is in a precarious position between domestic fragmentation and geopolitical competition. Iraq’s sectarian power dynamics and exclusionary politics post-2003 undermine national cohesion. In this context, Iran and Türkiye’s competing engagement models are critical and Türkiye’s Development Road involvement represents more than infrastructure; it is a litmus test for Iraq’s ability to rebuild national unity, recalibrate regional relations and reassert strategic agency. Yet at the same time the Development Road, despite its economic promise and opening new possibilities, is vulnerable to internal gridlock and regional rivalry.

Iran could stabilize Shiite heartlands. For Türkiye, it aligns with an economic integration strategy. If implemented inclusively, the corridor could foster interdependence and reconciliation. Ultimately, Iraq’s recovery depends not just on infrastructure but on political will and institutional reform. The Development Road offers a pathway toward regional relevant, but only if Iraq can traverse its internal divisions and reclaim control over its future. Only through reconciliation can Iraq shift from a geopolitical battleground to a regional bridge.