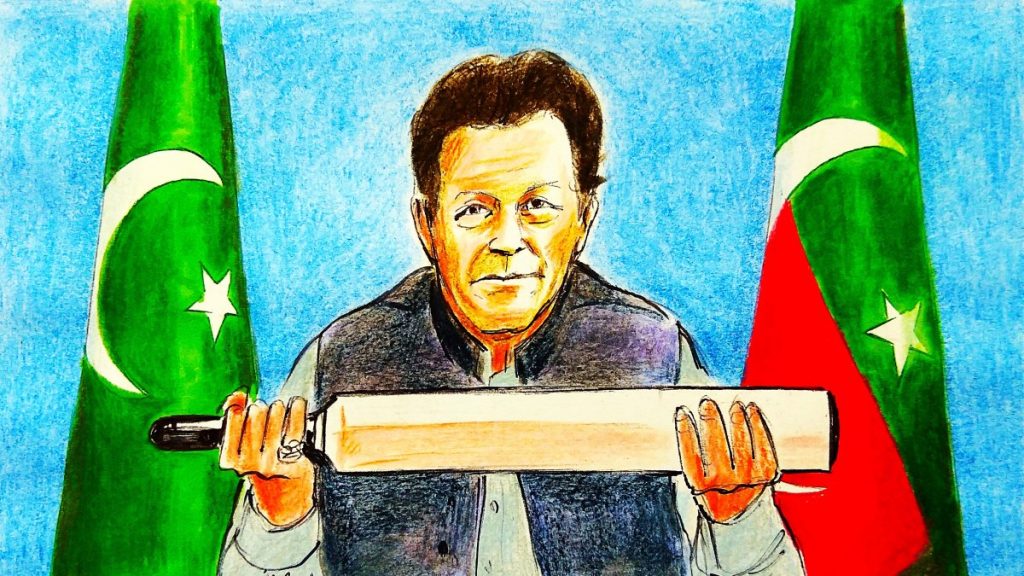

Imran Khan, the hero of Pakistan’s cricket World Cup victory in 1992, is renowned for his fighting spirit, which has won him adulation across the world. He was a gritty captain who inspired his men to stage stunning comebacks in near-defeat situations, especially against archrival India. Endowed with handsome looks, he also had a large autograph-seeking female following whether they were interested in cricket or not. Celebrities and politicians wanted to be seen in his company. It would have been amiss if he had not tried to carve out a larger national role using his sports stardom.

The political journey began in slow motion for the strike-fast bowler, one of the most feared in his days, after he set up his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, which espoused ideals of social justice and challenged the established parties of Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif.

Despite serious public dissatisfaction with inefficient governance and the politics of financial greed in the country, his party did not succeed instantly. It was clear that scoring in politics was going to be an entirely different contest than winning cricket matches. The PTI failed to win any seat in the 1997 National Assembly elections, and only Khan managed to win a seat in the 2002 elections. Neither Nawaz Sharif nor Benazir Bhutto considered Khan a serious opponent, and he had a long way to go to prove his political maturity. He had to learn how to manage the powerful elites and competing institutional interests. His rhetoric against corruption and incessant attacks on the alleged failings of the character of his major political opponents may have pleased a section of the population, but that was never going to be enough to secure him a parliamentary majority.

It took him over two decades after entering politics to finally become prime minister in August 2018. His cause was helped by the Supreme Court’s disqualification of Nawaz from office in 2017 over corruption allegations in the wake of the “Panama Papers” leak in which many world politicians, business figures and celebrities were caught. Nawaz’s Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) and Benazir’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) labeled Khan as the “ladla” (favorite boy) of the influential military establishment.

Against the establishment

Assuming that Khan was helped by the “establishment” in his political ascendance, it did not take long for him to fall foul of the powers that be.

In April 2022, Khan became Pakistan’s first prime minister to be removed in a dramatic parliamentary vote of no-confidence brought against him by the Pakistan Democratic Movement alliance, which included most of the country’s influential political players. Instead of going out quietly and waiting for more favorable conditions to make another bid for power, Khan decided to capitalize on a sympathy wave to launch a counter-offensive.

Pakistan, under Khan’s premiership, managed the COVID-19 crisis relatively well, and his welfare initiatives like the Sehat Card, a flagship scheme for universal healthcare and a shelter home scheme for the poor, won immense praise. But his overall record of governance was not extraordinary. Indeed, he would have found it difficult to win the next election had he not been removed via the parliamentary vote.

He appeared to lack political flexibility and displayed flaws in administrative acumen. In hindsight, it is safe to say that Khan did not inspire confidence in the elite circles as he began to be seen as overambitious and someone who would upset the institutional balance of power in the nuclear power state. It was reported that he wanted to introduce electronic voting machines, a huge move that seemed to lack political consensus.

On the issue of corruption, it would seem that he moved too fast and came in direct confrontation with powerful opponents in the early days of his premiership.

International enmities

Khan faced two extremely sensitive geopolitical challenges during his premiership. The first was India’s revocation in August 2019 of Article 370 that allowed the Jammu and Kashmir region (divided between Pakistan and India but claimed by both in full) a limited form of autonomy under the Indian constitution. Relations with India deteriorated rapidly, with Khan cutting off trade links with the neighbor and imposing a ban on Bollywood movies. It has been reported that some vested interests within Pakistan were in favor of a rapprochement with India, but Khan put his foot down. The issue is stalemated even though Khan has not been in power since 2022, which clearly shows how sensitive the matter is.

The second challenge was the so-called Abraham Accords between the Jewish entity and some Arab states manipulated by the Donald Trump regime. Unconfirmed reports have spoken of pressure on Pakistan from the pro-American Gulf states to recognize Israel. Khan reportedly rejected moving in that direction, knowing how foolhardy and self-destructive it would have been due to the overwhelming pro-Palestinian public sentiment. Some powerful elements wanted to pave the way for Saudi Arabia’s normalization with the Jewish entity by using Pakistan.

The downfall and the support

It is unclear what ultimately led to the PTI government’s downfall, but it led to an outpouring of support for Khan. His party sought to benefit the mood by building public pressure, a strategy that ultimately backfired because it made his opponents more determined to keep Khan out of power. Looking back, it becomes clear that Khan misjudged the level of public support and the appetite for street protests among ordinary Pakistanis.

In the campaign against his ouster, Khan was never surefooted in what kind of political fight he sought. The PTI’s social media campaigns have clearly been effective, but their success does not necessarily favor Khan’s future politics. Despite Khan publicly professing respect for the institutions, the power elites are suspicious of his intentions.

He initially blamed the United States for his ouster, saying Washington was against Pakistan pursuing an independent foreign policy, citing the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and other issues as examples. Pakistanis strongly approve of his position against America’s wars against Muslim countries and U.S. meddling in Pakistan. His uncompromising stance against the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan and the so-called war on terror inside Pakistan is much admired.

However, there is a contraction in the PTI’s strategy when Khan’s public views on the West are taken into account. Khan’s supporters in the U.S. have lobbied ranking Zionists in the U.S. Congress and pro-Israeli opinion makers to get him out of prison. Maybe it is desperation, but these moves will impact Khan’s future politics.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has so far shown that he is a stable hand and, unlike his elder brother and three-time prime minister Nawaz, is not prone to developing differences with the army as an institution. The current ruling coalition of the PPP and PML-N and their smaller allies looks confident. The 2022 fiasco and its aftermath have, however, reinforced the need for political parties and institutions to know their limits. There appears to be greater awareness of the pitfalls of confrontation on all sides. It is a welcome development that the government and PTI leaders have entered into reconciliation talks to reduce political tension in the country. These talks may provide an opening for Imran Khan to reach some accommodation with the power elites. The strategy of street mobilization would only further spoil the political pitch for him.