The Ottoman Empire exited World War I with the Armistice of Mondros on Oct. 30, 1918. Following this, the occupation of Ottoman territories, particularly Istanbul, was initiated by the Entente powers. At the Paris Peace Conference, the peace treaty was postponed as the Ottoman Empire’s territories could not be shared. In this process, as a result of the occupations of the Entente powers in violation of the armistice, Turks in Anatolia and Thrace began resistance by establishing and organizing up to 400 defense societies. These organizations held more than 30 congresses across the country and formed the social infrastructure of the National Struggle. Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s departure to Anatolia with his headquarters as the 9th Army Inspector with wide powers gave a new dimension to the movement of the Defense Law and from then on, the resistance movement managed to gather under a single roof and leader with the same goal in mind.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire was ruled by a constitutional monarchy and the 1876 Code of Laws was in force. The Parliamentary Assembly was dissolved on Dec. 21, 1918, but due to the political conditions, it was not announced when elections would be held. While organizing the resistance on the one hand, the Associations for Defence of National Rights (Müdâfaa-i Hukuk Cemiyetleri) raised the demand for general elections and the opening of Parliament, which was a constitutional obligation, and forced the Istanbul government. In December 1919, the Ottoman Parliamentary Assembly was opened in Istanbul and the Entente powers responded to the Assembly’s declaration of the National Pact (Misak-ı Millî), which set the final borders to which the Ottoman Empire could withdraw, by officially occupying Istanbul on March 16, 1920. The Ottoman Parliament was also raided and some of its members were arrested.

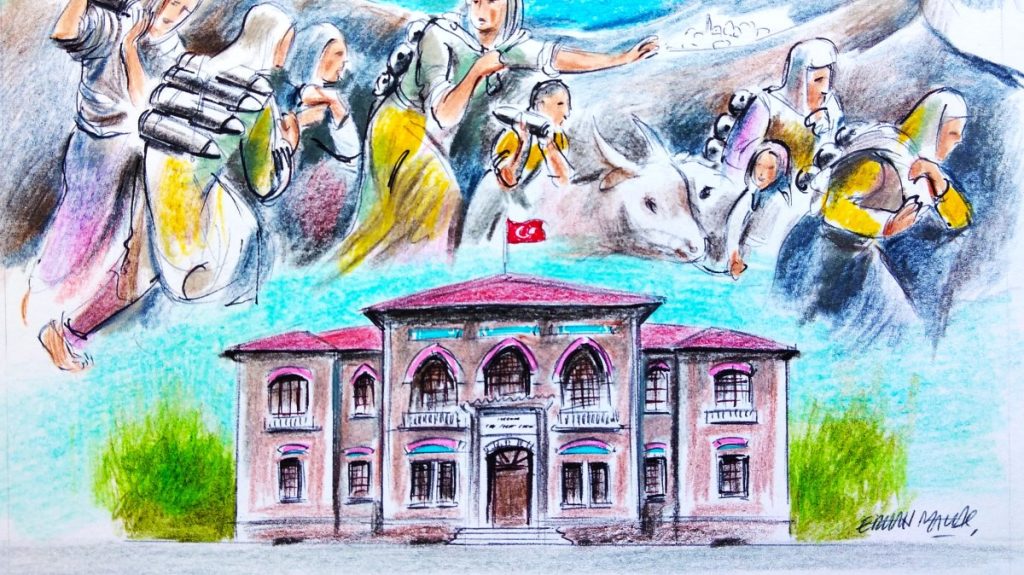

On March 17, 1920, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, as the head of the Delegation of Representatives, announced that Parliament would convene in Ankara. With the elections renewed throughout the country, the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye (TBMM) was opened in Ankara on April 23, 1920. The Grand National Assembly was opened as a continuation of the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies (Meclis-i Mebûsan) and became the symbol of the unity and integrity of the homeland, the sovereignty and independence of the nation against the invasions by adhering to the Sultan and the Constitution. The fact that the Assembly continued its work without breaking the legal and ideological contact with Istanbul was characterized by some authors as the Third Constitutional Monarchy.

On April 24, 1920, elections were held, and Mustafa Kemal Pasha was elected president of the Assembly. Abdulhalim Efendi, Çelebisi Abdulhalim Efendi of Konya Mevlana Dervish Lodge and Cemaleddin Efendi, Çelebisi Cemaleddin Efendi of Hacı Bektaş, the leaders of two important Sufi branches in Anatolia, were elected as deputy presidents.

A government was formed in the Assembly in a short time. First of all, the resistance against the enemy occupation was organized and supported, and new armies were formed. As a result of the Battles of Inönü, the Battle of Sakarya, the Great Offensive and the victory in the Battle of Dumlupınar, the Grand National Assembly government succeeded in expelling the occupying Greek forces from Anatolia. With the Mudanya Armistice, the military aspect of the National Struggle came to a close.

This political and military success gave the TBMM political and moral superiority over Istanbul. The fact that the governments of Ankara and Istanbul were invited separately to the Lausanne Peace Conference created a crisis of representation, and this crisis was resolved by the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye on Nov. 1, 1922, with the abolition of the Sultanate. Thus, Parliament confirmed that it was in control of liberated Türkiye and the delegates of the Turkish Grand National Assembly represented Türkiye at the Lausanne Peace Conference. At the end of the difficult negotiations, the signing of the Lausanne Peace Treaty on July 24, 1923, ushered in a new era of peace for Türkiye. The First Parliament, which fought and won the National Struggle, decided to go to elections again in April 1923, and the peace treaty was ratified by the Second Parliament in August 1923.

History that is not forgotten

The opening of the TBMM in Ankara on April 23, 1920, 105 years ago, and the struggle it waged and succeeded in, contain important and meaningful messages for today. First of all, the sensitivity of the Turkish nation on the issues of independence and freedom must be underlined. It has proven that the Turkish nation does not hesitate to fight against the most powerful states in the world when they are jeopardized. Therefore, in the Türkiye of the 1920s, there was a powerful “state, homeland and nation consciousness,” and if the state was in danger, the nation would take the initiative by organizing itself and taking matters into its own hands.

As a matter of fact, the Turkish nation demonstrated that its stance had not changed by taking to the streets to protect its state against the coup plotters on July 15, 2016. It is also evident that 105 years ago, despite all the adverse conditions, the nation and its organizations from all walks of life gave profound meaning and value to the concept of the “national will.” They were determined and persistent in holding general elections and opening the National Assembly.

Even in the most difficult times for the country, decisions concerning the life of the state and the nation were made not behind closed doors or by secret organizations or parties, but openly by representatives of the country who gathered, consulted and deliberated. They did this as a reflection of both their democratic maturity and their religious convictions. Verses from the Holy Quran recommending consultation were hung on the walls of the Assembly.

The First Assembly was composed of prominent members from each constituency, representing different political views and parties. However, they were united around the idea of the “salvation of the homeland” in Ankara, and there was no party conflict or partisanship until the struggle was won. It was as if the political struggle had been postponed until after the victory.

During the years of the National Struggle, the TBMM succeeded in creating a strong national front against imperialism that embraced all segments of society, ensured national unity and solidarity, and excluded no one. Thus, it adopted a policy of minimizing political and ideological differences as much as possible.

One fact that is often overlooked today – perhaps because more than a century has passed – is that the TBMM viewed the National Struggle in Anatolia as part of a broader struggle for the Islamic world and succeeded in rallying Islamic public opinion to its side. It is essential to note that this was not merely a propaganda effort, but rather a more comprehensive strategy aligned with the prevailing understanding of the time. In fact, despite not being free or independent, significant material and moral support for Türkiye’s National Struggle emerged from across the vast Islamic geography under the colonial rule of England, France and Italy. This support, which disturbed the colonialist powers and influenced Türkiye’s policies, represents an important yet often forgotten international dimension of the TBMM and the National Struggle.