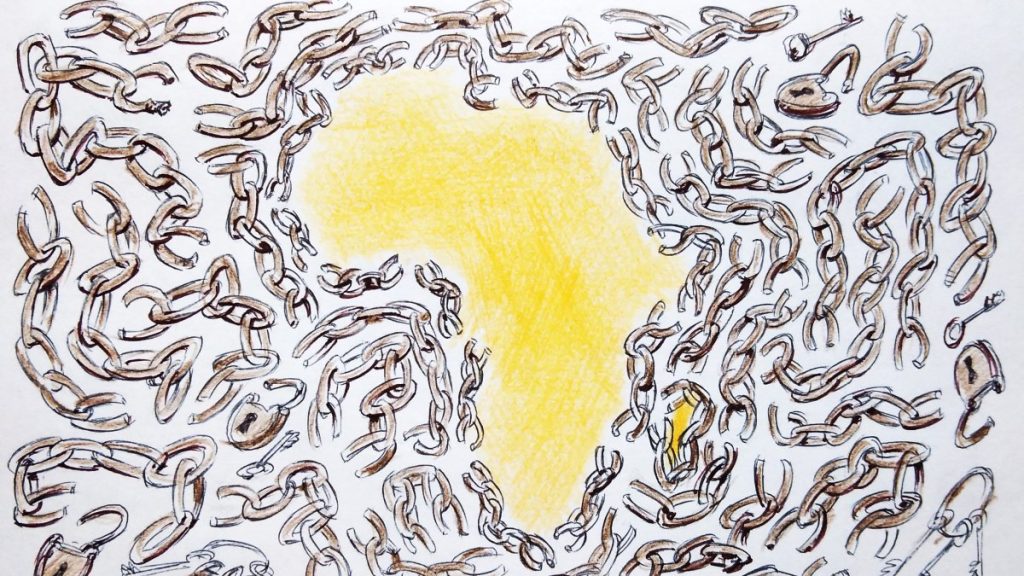

Across the continent of Africa, we have been witnessing the burning of French flags and the overnight closure of military bases. Once the dominant power across much of the continent, France now watches its influence wane at an unprecedented pace. The closing of French military bases in Senegal and the termination of defense agreements in Chad reflect a larger pattern of rejection; a continent shaking off the remnants of its colonial past and the structures of external domination.

France’s retreat from Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger marked the beginning of this unraveling. Disillusioned by the prolonged presence of French troops under the guise of counterterrorism, these nations opted to sever ties. Senegal’s recent decision to shut down a permanent French military base is a significant blow, given its history of stability and alignment with Paris. Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye’s emphasis on sovereignty and the removal of foreign troops highlights a growing continental desire. Chad’s decision to end its defense cooperation with France underscores the erosion of trust in Paris. Once a critical partner for France in the Sahel, Chad is now charting a new path. Together, these moves signify a rejection of the neocolonial dynamics that have long characterized Africa’s post-independence history.

France’s historical trajectory in Africa casts a long shadow over the current transformation. Its dominance on the continent dates back to the 17th century when it established trade posts in Senegal, gradually expanding to control vast swathes of West and Central Africa. By the 20th century, French territories encompassed over 11.5 million square kilometers. Policies of assimilation imposed French language, culture and governance, embedding them deeply into African societies. Many African elites, educated in French systems, internalized these influences, with some resisting independence altogether. This legacy persists in subtle forms, from economic agreements tied to the CFA franc currency to continued French military presence, all of which reinforced perceptions of paternalism and control. However, decades of unrest, dissatisfaction, and shifting global alliances have begun to dismantle these structures.

At the heart of this transformation lies the African public’s discontent with France’s policies. For decades, Paris maintained its grip on former colonies through military presence, economic ties and political influence. Branded as partnerships, these arrangements were often seen as extensions of colonial control. French businesses dominated local economies, while French troops, meant to ensure security, became symbols of paternalism and resentment. The revolts in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger – often referred to as the “anti-French wave” – were not isolated incidents. They marked the culmination of years of frustration with France’s perceived arrogance and ineffectiveness. In Mali, accusations of indifference in combating insurgencies fueled anti-French sentiment. Burkina Faso questioned France’s motives, and Niger’s military junta expelled French troops shortly after overthrowing a French-aligned government.

New actors in African stage

As France’s influence recedes, alternatives like Türkiye, China and Russia have stepped in. As is known, Russia’s Wagner Group provides military support in countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, while China’s extensive investments in infrastructure offer African leaders a seemingly more attractive economic alternative. Türkiye, a rising regional power, has gained traction through not only valuable humanitarian aid, education initiatives and business cooperation but also significant infrastructure projects such as highways and railways. These developments have bolstered Türkiye’s image as a versatile partner offering tangible benefits. Together, these shifts have given African nations more leverage, enabling them to push back against traditional powers like France.

The numbers tell a clear story. Between 2010 and 2023, Chinese investments in Africa surged by 200%, exceeding $200 billion annually. Meanwhile, France’s share of foreign direct investment has steadily declined. This economic realignment is redefining partnerships across the continent.

France’s loss of influence extends beyond military withdrawals or canceled agreements; it reflects the waning of French soft power. Once a dominant cultural force, France now struggles as African nations increasingly prioritize their own languages, cultures and traditions. Yes, French remains an official language in many African countries, but even this is being challenged. Local languages are gaining prominence in education, media and public life, while younger generations turn to English for broader global opportunities. The cultural bond that once tied France to its former colonies is fraying.

The roots of this rejection lie in history. France’s colonial legacy in Africa is one of exploitation and control, a reality many Africans have neither forgotten nor forgiven. Even when France framed its actions as supportive, they were often seen as self-serving. With nations like Senegal and Chad joining the chorus of discontent, the tide has decisively turned. African leaders and populations are increasingly unwilling to accept arrangements that do not prioritize sovereignty and development.

What lies ahead is uncertain, but the direction is clear. Africa is stepping into a new era, preferring partnerships that prioritize dignity, respect and mutual benefit. While rejecting neocolonial structures is essential, Africa must also guard against over-reliance on new actors that might replicate similar dependencies. For France, this transformation is a profound challenge to its global ambitions. Africa has long been central to its foreign policy, providing resources, markets and strategic depth.

The closing doors in Africa are more than a rejection of France. They are a declaration by a continent determined to define the coming centuries. As the echoes of colonialism fade, Africa’s voice grows louder, calling for equality and a future written on its own terms.